If, as Chekhov almost said, in Act One you have an impotent man, then he must achieve an erection by the final act.

This was the first line of my dissertation for my MA in Creative Writing.

If you’re not familiar with the quote from Checkhov, what he actually said is that “if in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise don't put it there.”

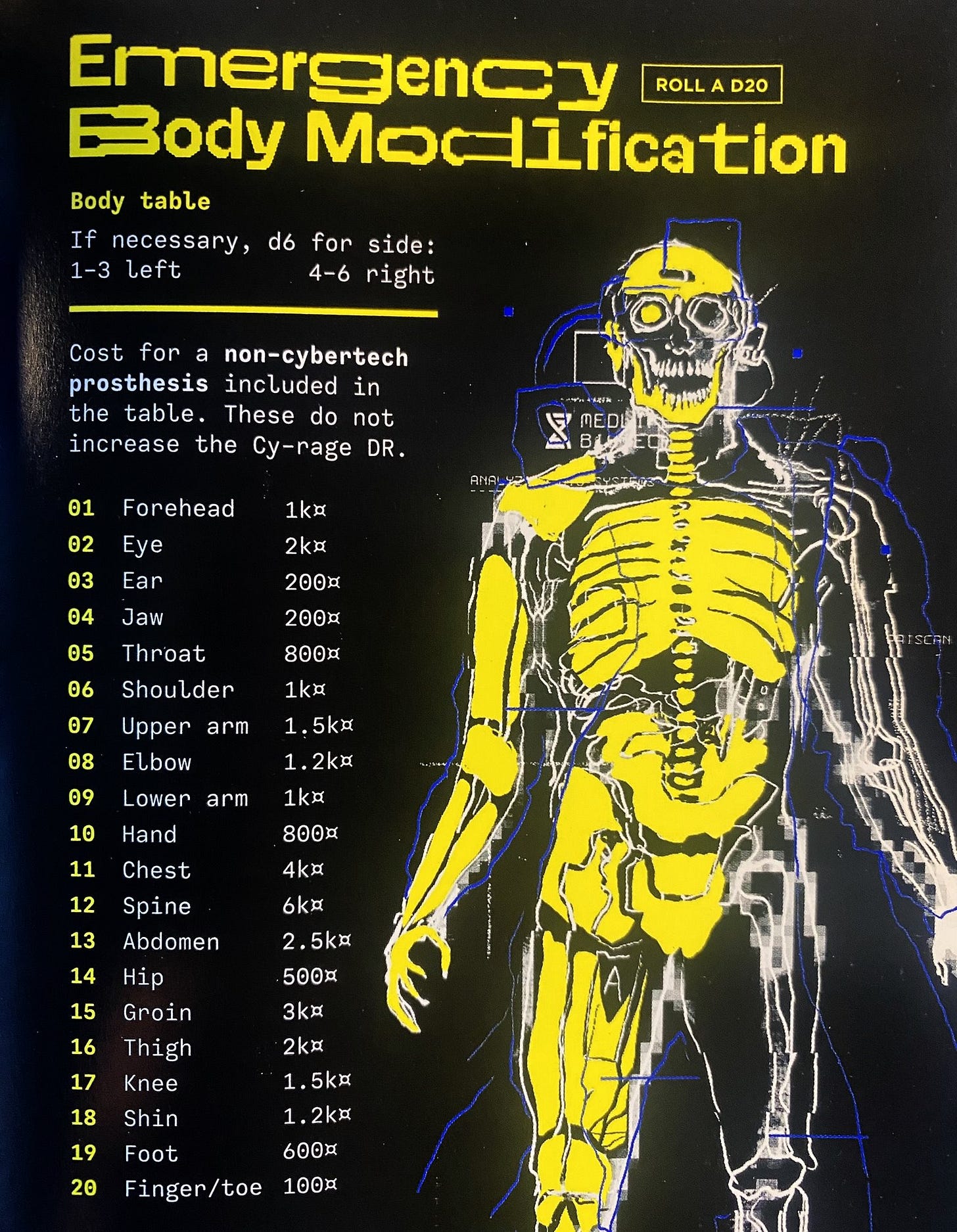

I was referencing the first successful story that I’d written, which had secured my entry on the course. It was about an impotent cyborg. The story worked because it had a definite narrative arc - like Checkhov’s pistol, my cyborg had to get it up by the end of the story. And given that it’s hard to write about a robo-penis with erectile dysfunction in a serious manner, there had to be humour in the way I told it.

I promise I am not telling you this in a desperate effort at robo-penis clickbait. It’s to illustrate a point. In both the story itself and my dissertation I was playing with the rules - of stories and of the power structures inherent in submitting work for assessment - both because it was fun (and, to my mind at least, funny) and because it allowed me to build something new (or at least to say something old in a new way).

In the words of Michael Rosen, poet and bona fide National Treasure, “I believe play is key to helping us develop and reach our full potential.”

And I believe that this is true in every aspect of life - home, workplace, school, everywhere. We can (and I will) wrap it up in productivity terms so we can all pretend that this is serious stuff (it is) that plays an important role in our function as Serious Adults (it does). But I’ll let you into a secret: it also makes life MORE FUN. And if you don’t have time for fun in your life you may as well be dead.

I’ll be honest, I’ve re-written this post a couple of times now. It keeps turning into an academic essay where I throw out lots of evidence about why playing is important. Which I think stems from a) my own insecurity about the fact that I play lots of geeky games and b) the fact that contemporary society tends to devalue play.

There is another name that we use for play, though, that allows us as Serious Adults to legitimise it.

In Emily St. John Mandel’s brilliant novel Station Eleven, part of the story follows the Travelling Symphony, a group that travels around a future dystopian world, devastated by a pandemic, performing Shakespeare. On the lead caravan are stenciled words stolen from an episode of Star Trek Voyager: “Because Survival is Insufficient”. It’s a quote about the importance of culture (be that Shakespeare or Star Trek) - and, as my friend Lenny points out in his Tedx Talk about play, when we become adults “we schedule play in our diaries and call it culture.”

Culture is important. But it can be a distracting word, coming with lots of baggage. Is hosting a games evening culture? Is playing with Lego culture? A video game? Skateboarding? Avoiding stepping on the cracks BECAUSE THE FLOOR IS LAVA?

As a Serious Adult, it’s easier to justify participation in some of these activities than others (imagine if I told everyone that I’d taken a year long career break just to play video games rather than write a novel. Sometimes I do, just to see their reaction). And as any parent will tell you, children are the ultimate prop for playing - with a child you can ostentatiously not step on cracks on pain of getting eaten by an alligator, but try doing that as an adult on your own and you get weird looks, however much fun it is.

People used to play more. In his seminal 1972 paper “The Original Affluent Society,” Marshall Sahlins argued that his study of still existing hunter-gatherer societies showed that prehistoric societies probably spent more time in organised forms of play rather than work. They were not seeking to maximise hunting productivity, but were “more concerned with games of chance than with chances of game.”

Survival is insufficient. Play makes life worth living.

Philosopher C. Thi Nguyen has said that “the real world’s this existential hell-scape of too many values, and games are like this temporary balm.” In a world where it’s difficult to know what’s the right thing to do on very basic questions (should I buy avocados?), games and play offer very definite rules (don’t take a motorbike to a road bike race, even if it makes you go faster) where the values are always clear (screw over your opponents by making them pick up as many cards as possible - Uno).

But here’s the thing: play also makes us better at living.

Michael Rosen argues that play does two important things - it helps us to deal with the “mind-boggling level of change” we face every day by teaching us to cope with the unexpected, but it also teaches us that we can change the rules:

What I’m saying here, you see, is that play can create new order […] through inventiveness we often create, develop, use and adapt order - breaking down the existing structures of knowledge or skill, the sequences that hang together or make some kind of sense - and re-shape them into new structures.

Like turning Chekhov’s famous rule for storytelling about the presence of a gun in act one to instead be about an impotent cyborg. Or playing an online game about the folding of proteins to try and discover real-world biological innovations that can cure disease (it’s a real thing that you can go and try right now!)

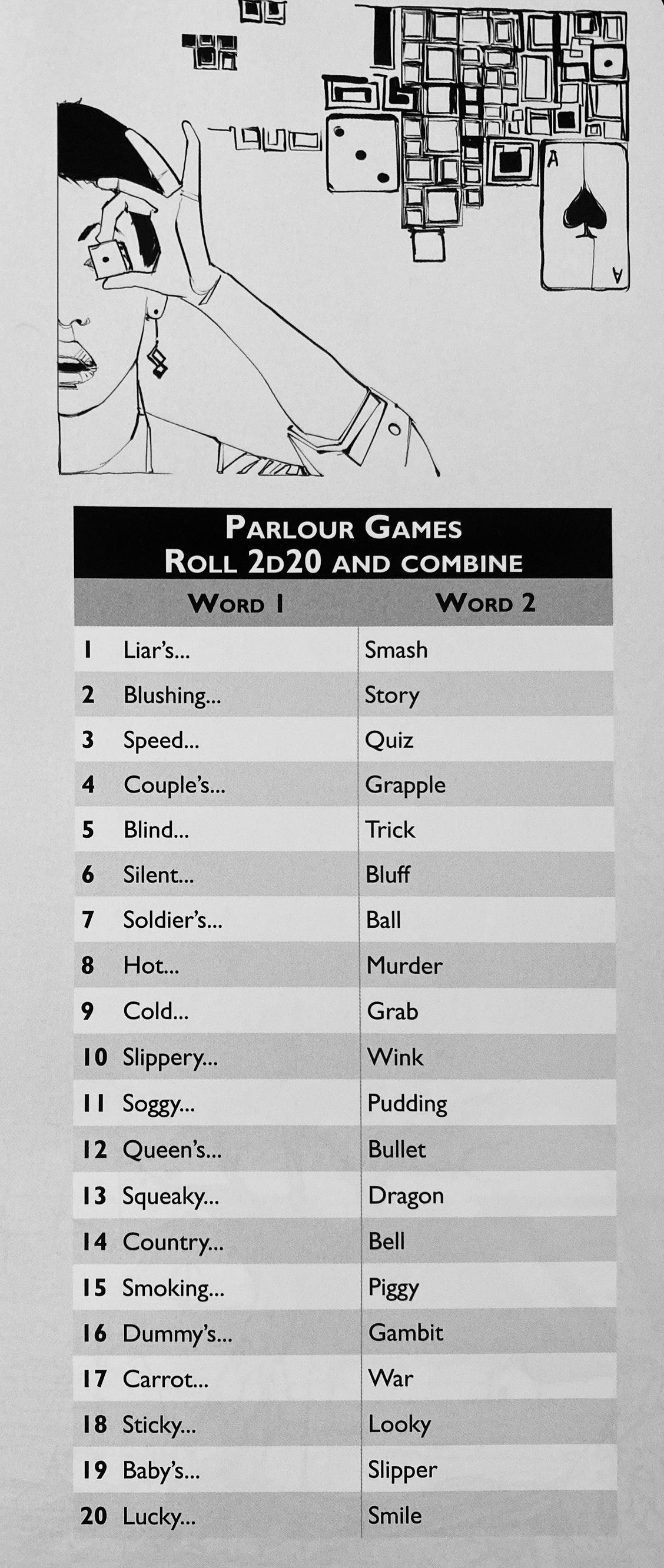

Do you have a friend? Then great, you can play something with them. Don’t have a friend? Also not a problem - play a sport, go to a gaming evening, join a quilting group. Do an icebreaker at your next corporate event (you know, the organised fun events that everyone pretends to hate). Whatever it is, that shared endeavour of playing at something will give you a ready made community of friends. You don’t even need to talk about yourself if you don’t want to, you can just talk about whatever it is you’re doing.

So: my exhortation to you today is to go and play. See how much of the dishwasher you can unstack while holding your breath. Doodle with two different colours. Imagine the craziest invention you can, to do the things in your life that bore you. Challenge a friend or family member to do the same. Have some fun. Live.

————————————-

INPUTS

What I’ve been reading/watching/listening to/thinking about…

Podcast: I’ve been re-listening to Ezra Klein’s interview with philosopher C. Thi Nguyen (he of the existential hellscape quote, above), who writes about the philosophy of games. That podcast is behind a paywall now, but you can also listen to him interviewed on Sean Carroll’s Mindscapes. In addition to the beauty of games, he also talks about the gamification used by tech solutions e.g. Twitter/X - and how they play you in order to incentivise you acting in a certain way. Honestly, I could listen to Nguyen talk all day.

- Short Stories/Obituaries: Robert Coover died at the beginning of October. A master of the postmodernist short story, and a writer whose entire corpus is about playing with the rules. He was heavily influenced by Kafka, and Kate Atkinson wrote the introduction to the Penguin Modern Classics edition of his seminal collection, Pricksongs & Descants. An important writer who is not widely known, but who influenced and continues to influence writers you probably do know. Also: read obituaries because “They are just like biographies, only shorter. They remind us that interesting, successful people rarely lead orderly, linear lives.” - Charles Wheelan

- Learnings on life: “Somewhere along the way, you realize that no one will teach you how to live your own life.” 18 Life Learnings from 18 Years of The Marginalian. The Marginalian has been offering pithy insights about living from the writing of others for 18 years. It’s a wealth of content that I’ve returned to on and off for the past ten years, whenever I’ve felt the need for some spiritual comfort about life.

————————